In recent months, inflation has been souring. Governments and central banks across the world have been trying to tame the rate of price increases. In most cases, with little to no effect. Earlier this month, the annual US inflation rate hit a 40-year high of 8.6%. This means that on average, prices of goods and services rose by 8.6% from a year ago. It would be a good starting point for us to understand how we actually got to this point to understand how this situation would possibly unravel over time.

For a significant period of time, global interest rates were extremely low. Possibly close to zero. This started with the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. The collapse of Lehman Brothers sparked panic and there was this great distrust in the financial sector. This then set off a period whereby the US Federal Reserve (The Fed) went on this unprecedented quantitative easing where they injected the economy with large amounts of money. This was in large part due to The Fed purchasing assets from the market. This had the effect of placing cash in the hands of the entities which they bought them from. The Fed Funds Rate, a barometer for interest rates across the US and many parts of the world, was set close to zero. Think of it from an extremely simplistic view (though this may not be the most accurate representation of what is going on). If the central bank is willing to lend money at close to zero interest, how can commercial banks stay competitive and charge significantly higher than what The Fed was willing to offer? On a global scale, why would borrowers then want to borrow money from lenders in Singapore if they could obtain a lower rate in the US? This set the tone for a period of extremely cheap financing. This is why borrowing rates like mortgage rates have been so low over the past decade and a half. In fact, I’ve known of individuals who purchased an HDB flat and decided to finance the flat using a 15-year HDB loan with a fixed interest rate of 2.6% when the private mortgage rate was hovering below 1.5%. The rationale was that they believed that the private mortgage rate would eventually rise above 2.6%. Fast forward almost 15 years later and that decision did not pay off at all. The private mortgage rate never got close to 2.6% for the majority of the loan tenure. This is the paradoxical nature of the world that we live in currently.

The quantitative easing that started in 2008 set the tone for more than a decade of cheap financing. It thus favoured risk-takers and spenders rather than those who were risk-averse and savers. If you were willing to stake your monies in assets, you were usually rewarded. Occasionally very handsomely. How handsomely one might ask? Look at this chart of the Dow Jones Industrial Average. In 2008/ 2009, the index was hovering around 8000 points. In early 2022, the index crossed 35,000 points.

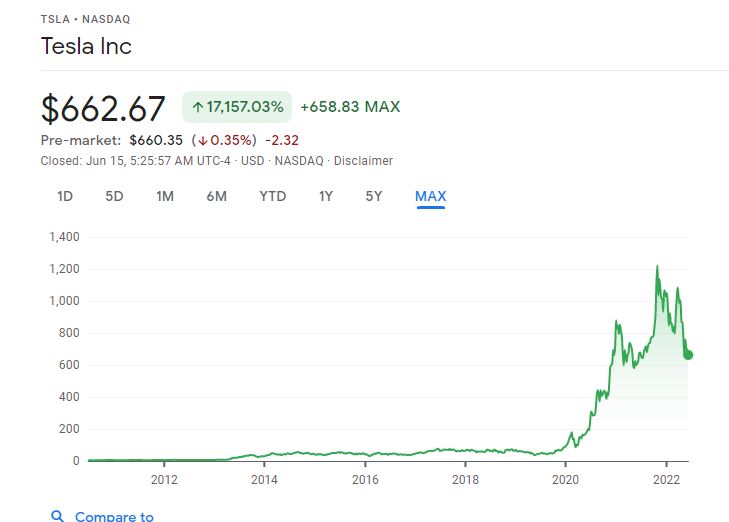

Looking at the stock price of a company like Tesla would perhaps tell us how buoyant the market sentiment has been for the last decade and a half. Tesla stock started trading at a mere couple of dollars. In November 2021, the stock price of Tesla soared past USD$1,200. That is a 30,000% price increase over 12 years.

Such cases are reasons why I always believe that an individual’s investment portfolio should not just be centred around properties but should definitely include assets like stocks. While there is usually less use of leverage when it comes to investing in stocks as compared to investing in property, the returns over some counters are truly phenomenal. If an SGD $1 million property were to increase by 30,000%, the property would be worth SGD $300 million. Of course, diversification would taper the returns greatly but it would not be difficult to find investors holding onto tech counters like Tesla, Facebook (or now most recently, Meta) or Apple.

So the simple question is, did the intrinsic value of companies like Tesla increase at the same rate as did their stock prices? The simple answer is no. Far from it. Yet the stock price rose considerably. The reason was that there was a lot of spare cash in the system. Governments were handing out money, interest rates were low and hence businesses were often borrowing money to expand. When it was perhaps time to deleverage, there were elections and then the subsequent pandemic. The Fed never got down to unwinding all the quantitative easing that it started during the 2008 financial crisis. Another key factor was that a strong economy wins elections and hence since the appointment of The Fed chief was done by the president, this would mean that the president could appoint someone who he thought was in line with his overall policies. While the Federal Reserve is supposed to be bipartisan, the appointment of The Fed Chief was at the discretion of the sitting president. In short, it is always in the interest, not only of the American people but of the sitting president to have a strong economy.

This then leads us to today. Almost 15 years have passed since quantitative easing started due to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. Since then, the US and global economy has never truly ever deleveraged. People are used to their governments placing monies in their bank accounts. People were encouraged to spend. In Singapore, no amount of additional stamp duty can deter property buyers. COE prices for cars crossed the SGD$100,000 mark and yet analysts predict it could go even higher. The mindset is “if the economy was so good during the covid-19 pandemic, surely it would be roaring when the economy opens up post-pandemic”. The truth is less straightforward. Inflation is a huge issue. It will remain a huge issue for a significant period of time. How often are we hearing the term “better buy property now before it goes even higher” as compared to “the yields are good and hence this is a good property investment”. I understand that property is a tangible asset. However, just because it is a tangible asset does not mean that we can pay any price for a tangible asset.

So what is deleveraging?

In short, it is the removal of money from the system. There are essentially a few ways this can be achieved. This is a way that stubbornly high inflation like the one we are currently experiencing can be curbed.

1) Increasing interest rate

This would mean that the cost of borrowing would go up. It is going up at a very fast pace in the US. In the US the average rate for the benchmark 30-year fixed mortgage is close to 6%. Would such a rate present itself in Singapore? Possibly. Singapore is a price taker and our interest rates track that across the globe, namely the US, very closely. A high mortgage rate would also mean that fixed deposit and saving rates will correspondingly be high. Hence this encourages saving rather than spending. A simple demand and supply curve would explain that you would either have to curb demand or increase supply to lower prices, all things being equal. Throughout the past few years, governments have been trying to spur demand for the supply of goods and services that have remained constant. However, now that the pandemic has caused supply chain issues, the supply of goods has subsequently fallen and yet demand is strong, fueling an increase in prices. To taper demand, interest rates will need to be used to spur saving rather than spending.

2) Reducing the central bank’s balance sheet

The Fed is currently reducing its balance sheet. During quantitative easing, The Fed would purchase assets from entities. This would mean that the Fed would be putting cash in the hands of these entities, thereby injecting money into the system. Now they are doing the exact opposite. The Fed is reducing the assets that it holds. Selling securities has the exact opposite effect. Entities would need to fork out cash to purchase securities, thereby reducing the amount of cash it has on hand. This would curb expansionary appetite somewhat. The effects of this can be felt globally. Companies like Tesla in the US have announced job cuts and so have companies in Singapore like Shopee.

What will likely happen?

In the US, a recession is likely. The fact is that the US economy has been so reliant on cheap financing that it is unlikely that the unravelling will be smooth. In Singapore, we are so far past full employment that we have a shortage of workers in many industries. This is perhaps the ideal situation to lead us back to normalcy and pull the demand for workers lower towards a more sensible equilibrium. That being said, the time has perhaps come for property price rises to ease off. Mortgage rates are expected to rise significantly and I would think that we should see fixed mortgage rates of more than 3% come the end of 2022.

So is this a good time to be investing?

Perhaps. Well not now exactly but in every recession or cooling-off period opportunities would present themselves. I do think that interest rates will put a huge damper on the local property market as buyers would be cognisant of the fact that interest rates can go up pretty quickly. When property demand is low, buyers can have time to think rather than being pressured to make an immediate purchase. The issue is that there will always be “investors” who think that prices will always remain low and will once again “miss the boat”.

Personally, am I looking to purchase a property during a downturn?

I am not looking for a residential property. I think that the restrictive additional buyers’ stamp duties have shaped my buying behaviour. I might look to purchase a commercial property but the numbers will need to make sense. Other than that, I think it is a great time to be looking at the stock market whenever the market starts falling. Us humans have a tendency to overdo things. Just like a decade and a half of leveraging caused us to overbuy, when the recession comes, if it comes, the possibility for us to oversell is also very high.

The fact is, none of us can predict what the future holds. Investing is always about having the ability to hold onto the asset even in times of deleveraging. Because of the scale of the leveraging that came before, we must be prepared for a similar scale of deleveraging that is about to unfold.

Yours sincerely,

Daryl